| |

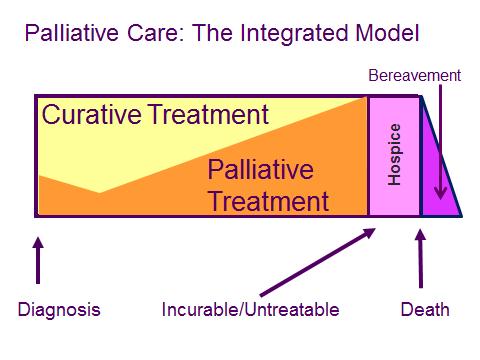

| Oct. 8, 2015 Integrated Palliative Care in Action: What does it look like?Because patients and providers will often mistakenly equate palliative care with hospice care, there is confusion as to what role palliative care may play for a patient who is still receiving or who desires disease-focused therapies. Ina previous article, the optimal model of palliative care was depicted as a simple graph.

The model above illustrates the integration between attempts to modify disease trajectory and assessments for unmet palliative needs, which span physical, emotional, social and spiritual realms. This model is designed to allow medical teams to provide complete care of the patient and improve overall quality of life. The following patient examples demonstrate this model working at its highest level, where conversations start early and guide the later transitions in care planning. When Renee* was diagnosed with an aggressive lymphoma in early 2013, like many patients, she was focused on a cure. Her disease showed some response to the first-line chemotherapy regimens. By June, unfortunately, her cancer was growing despite those therapies. Renee made the decision to transition her care to a specialized cancer center. During her first hospital stay for a new chemotherapy regimen, she requested a palliative care consultation. Her oncologist and hospital physician were surprised, but consulted the palliative care team nonetheless. Renee spoke of her desire to continue pursuing disease-modifying therapies, while planning for the possibility that her cancer might not get better. She discussed her work in patient relations at a nearby hospital, and how often she observed people growing more and more ill without open conversations about what was really happening to them. Renee spoke of hip pain that was worsening and making it difficult for her to be as active as she wanted to be. The team examined her medications and recommended adjustments during her hospital stay, which improved her walking significantly. Renee expressed the desire to follow up in the outpatient palliative clinic, and she has done so for the past six months. The physicians and nurses have supported Renee through subsequent chemotherapy and radiation treatments by addressing ongoing pain and nausea, listening to her concerns about how her husband is coping with her illness and discussing when, in her view, the burdens of further treatment will outweigh possible benefits. She hopes to have the social worker speak with her husband about the questions that he has regarding what her path looks like if the cancer can be controlled, and if it can’t. In general, palliative care has had a more natural relationship with oncology than with other medical disciplines, but this is changing. Consider the story of Betty*, an elderly female with severe COPD and heart failure. Her pulmonologist employed excellent primary palliative care practice by focusing on maximizing her physical function and initiating conversations about the progressive debility Betty would experience as a result of her illness. Eventually, the pulmonologist reached out to the palliative care clinic for assistance with managing her severe shortness of breath. Betty and her children developed a relationship with both teams that lasted for two years. When an interventional procedure led to difficulty with her breathing, Betty’s family faced the decision of whether or not to place her on a ventilator. As a result of the previous conversations with the pulmonary and palliative teams, the family understood the ramifications of intubation and did not believe that this would be consistent with Betty’s goals or wishes. With noninvasive breathing support, Betty’s breathing improved, and she was able to pursue acute inpatient rehabilitation to become stronger. The palliative care team remained involved in her care, helping to manage opioid medications that she used to ease her breathlessness. When Betty and her family needed more support at home, the palliative care team helped arrange for home hospice care. She spent most of the last 18 months of her life at home, with her family, and occasionally traveling to family reunions. Renee and Betty benefitted tremendously from early palliative care practice. Both pursued curative, disease-modifying therapies in conjunction with aggressive symptom management and future care planning. Both felt stronger and more active because the physical manifestations of their two diseases were addressed. For Renee, facing the uncertain outcome of her illness has been simpler because of conversations that are allowing her to plan how she would want to spend her final days if her cancer proves unresponsive. For Betty, when the ultimate path of her illnesses was clear, she and her family were empowered by the previous conversations with their providers to set limits on the type of interventions she wanted to receive. This model of health care, which integrates palliative care principles into patient evaluation earlier, is the goal. *The names of the patients have been changed to protect their privacy and comply with privacy laws.

| |